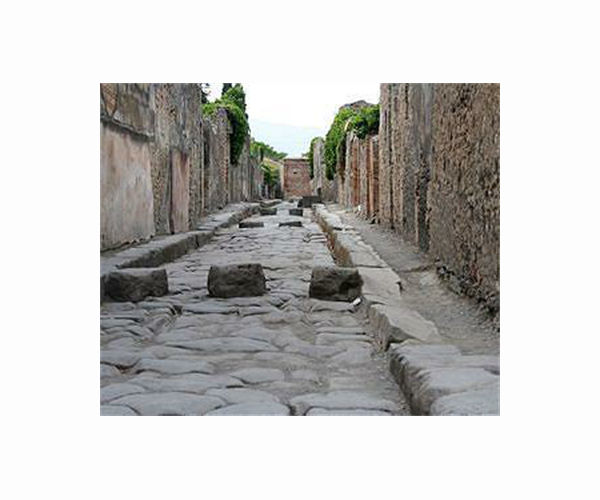

‘Ancient Roman’ solar roof tiles power the villa of Pompeii

Pompeii sheds light on the mysterious rites of ancient Rome thanks to terracotta-style solar roof tiles installed on one of its most famous villas.

The traditional-looking tiles feature solar photovoltaic cells, allowing the UNESCO World Heritage site to maintain its aesthetics while generating clean energy to illuminate the frescoes.

And while the project is still in its early stages, experts say the tiles could one day help historic city centers across Italy turn green.

The tiles look “exactly the same as the ancient (Roman) ones” found at archaeological sites and cities across the Mediterranean, Pompeii director Gabriel Zuchtriegel told AFP.

But while “Pompeii is a unique location because of its enormous size and complexity… I hope this will not be a unique project,” says Zuchtriegel, who wants the site near Naples to become a “real laboratory for sustainability.”

The plan combines emerging technologies with an extraordinary mural excavated in 1909 beneath deep layers of volcanic ash at the Villa of the Mysteries, which was buried along with the rest of the city when Mount Vesuvius erupted nearly 2,000 years ago.

The mural depicts female devotees of Dionysus – the god of wine and revelry – engaged in mysterious rituals.

They have intrigued scholars for decades, with some historians suggesting they are evidence that the lady of the house was a priestess whose slaves participated in cult rituals.

– Terracotta varnishes –

The fresco, which spans three walls and is one of the best preserved in Pompeii, is illuminated by special LED lights designed to bring the deep red, purple and gold images to life, without damaging the painted surfaces.

The lights are powered by electricity generated by the solar panels installed in October.

Ahlux, the Italian company behind the lamps, patented the system in 2022 and produces both curved and flat panels lacquered in terracotta tones.

The solar panels on the roof of the villa are flat and set between traditional ceramic curved tiles.

They cover a roof of 70 square meters, produce a maximum of 13 kilowatt hours and are linked to an environmentally friendly sodium battery, according to project manager Alberto Bruni.

Pompeii, which gets more than 15 hours of sunlight a day in the summer months, plans to expand its use to other villas at the archaeological site, he said.

Augusto Grillo, the founder of Ahlux, said the tiles are about five percent less efficient than a traditional solar panel.

“However, this nominal loss is offset by the fact that our panels heat up less in summer,” while traditional panels are covered with glass and can lose efficiency on very hot days, he said.

“The execution is very similar,” he said.

– Red tiled cities –

Several institutions have shown interest in the tiles, from the MAXXI Museum of Modern Art in Rome to the 17th-century Pinoteca Ambrosiana Museum in Milan, Grillo said.

“The problem is finding the funds,” he said, adding that many of Italy’s famous historic buildings are public or owned by Catholic institutions.

The cost is slightly higher than the price of a new roof and traditional panels combined — although the solar panels, which last between 20 and 25 years, serve double duty as they also act as a roof, Grillo said.

Project manager Bruni said the cost of the panels is “falling”, meaning they could potentially play a role in the wider ecological transition.

Italy is under pressure to make red-roofed cities such as Florence or Bologna greener as part of efforts to combat climate change.

The European Union aims to reduce CO2 emissions by 55 percent compared to 1990 levels by 2030, and will need to upgrade existing buildings to achieve this.

That’s a huge challenge for Italy, where some 60 percent of buildings are in the worst two energy categories, compared to 17 percent in France and six percent in Germany, according to Italian construction association ANCE.

“There needs to be some national and perhaps European co-investment to ensure that the very, very ambitious timelines have a chance of being respected,” Angelica Donati, president of the youth constructors’ association ANCE Giovani, told AFP.

“We have the most beautiful cities in the world, which means we need much more thoughtful interventions, and quickly. There is still a lot to be done.”