The Solar Power Portal team is attending the UK Solar Summit 2024 in London today (4 June). Our rolling coverage of the event can be found here. This article will be updated throughout the day as the event progresses.

An ‘absence of decision-making’ in government has been holding back the development of Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects (NSIPs) in the UK.

Gareth Phillips, partner at Pinset Masons, said that there are currently 35 NSIP projects registered with the Planning Inspectorate amounting to around 15GW of renewables capacity. “And this is just the tip of the iceberg,” he said.

The recent Written Ministerial Statement on solar farms “gives our opponents another stick to beat us with”, according to Alex Herbert, head of planning at Telis Energy. However, as mentioned by Chris Hewett in the UKSS’ opening discussion (below), the reality of the policy framework for NSIPs in the UK is “strong”, and the Ministerial Statement made no real difference beyond appealing to those looking for “anti-solar rhetoric”.

Local challenges

“It turns out that local politics is not stopped by national government approval for a project”, said Rosalind Smith Maxwell, director at Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners. Despite receiving a development consent order (DCO) and environmental and safety approvals, projects can still face opposition and delays at the local level.

Mark Noone, head of UK development at Elements Green, said developers can be guilty of “the assumption that you have a good site selection and so you’re going to sail through the approvals process. That’s increasingly not the case. And even with a new government and a new, stronger policy, I still don’t believe that’s an attitude [developers] can keep going with.

“Especially in an NSIP context, you need to get into the community with local people who understand the local area and priorities.” He gives the example of the Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire area, which is host to a number of NSIP projects and has experienced severe flooding. He says that an Elements Green project in the area met opposition from residents already concerned with the flooding in fields, in an example of the need for developers to engage directly with the land and its communities.

Maxwell said that developers should consider the “cumulative impact” which projects planned in the same area will have on land and communities. She referenced a statement from energy security secretary Claire Coutinho last month, who said: “I want to see more solar on rooftops and where that’s not possible, for agricultural land to be protected; and for the cumulative impact on local villages to be considered where they are facing a high number of solar farm applications.”

Maxwell said: “[Cumulative impact] has been the most recent negative [for solar PV] that has been used by Parliament. You then have to work together with your neighbouring developers…thinking about the cumulative impact on communities and cumulative benefit.”

She cited a project in South Wales on the site of a former coal plant next to a retired steel works – “it’s an anchor project for the regeneration of the whole area. It’s about reminding people of the just transition so they’re not scared of losing jobs; there’s going to be a hub of solar jobs and future-proof careers for you,” through multiple projects working together.

NSIPs and the Election

Panelists were asked what they want from political parties during the upcoming election:

“From the Tories, some honesty given what we said about the Written Ministerial Statement,” said Alex Herbert of Telis Energy. “If Labour get in, we need them to commit to the National Policy Statement (NPS)” – the planning guidance governing the development of NSIPs. “They’ve said that they’ll review the NPS within the first six months, but there’s no detail about what that actually means. Six months doesn’t really give them time to consult or change, so the assumption is that it will stay the same, but it would be helpful if they say that up front.”

Noone called for “clarity” from the Labour Party if it comes into power. “A strong, focused government that isn’t pandering to minority views.”

Phillips added that there are currently “2GW of solar projects just at utility-scale which [Keir Starmer] could sign off on, should he find himself becoming Prime Minister. It’s there, it’s done, they’ve had the recommendations from the Planning Inspectorate, a decision letter would have mostly been written – a decision could be made within a week. It’s that easy.”

Just over a year after its formation, members of the UK Solar Taskforce came together to analyse its progress and discuss emerging challenges in the solar energy sector.

One of the task force’s key objectives was to develop a UK solar roadmap. However, the dissolution of parliament ahead of the 4 July General Election has delayed government buy-in.

Panel moderator and co-chair of the Solar Taskforce Chris Hewett joked that “elections get in the way of government sometimes”. However, this is not a return to square one. The task force will workwith newly elected ministers and review the roadmap in relation to party ambitions – whoever that party may be.

Should they be elected, “Labour want to hit the ground running, they have very ambitious targets for our sector.” The election is a chance to “widen some of the roads, increase some of the speed limits” in the roadmap, Hewett added.

Grid connectivity

Gemma Grimes, director of policy and delivery for Solar Energy UK, noted that grid changes aren’t just necessary for large-scale solar developments to move forward; grid connection for rooftop solar must be improved to make households fit for the future.

Ben Fawcett, who was on the task force division focused on grid connectivity, said that data from DNOs is critical: “Data transparency should be a win-win for us all.” Furthermore, the task force has considered raising the technical limit thresholds to ensure that the expertise dedicated to projects is proportionate.

Skills shortage and the supply chain issue

When the task force was formed, there was a “huge amount to do” to establish and understand the state of the job market within the sector. Over the past year, the task force has unlocked that data and turned to questions about how best to educate the next generation of green workers. Is there a place for a solar-specific apprenticeship?

Solar Energy UK’s skills steering group is mapping out funding sources and identifying what the industry needs to do to make the most of it this year. Fawcett pointed out that large-scale manufacturing is unlikely to happen in GB, but manufacturing is only one way to generate jobs.

Industry take on GB Energy

Everyone is in agreement that funding for the sector is a positive thing. However, Alexandra DeSouza said, the reality is that the amount suggested (around £5 billion left after an initial £3.3 billion goes to the Local Power Plan) will not go far.

“The devil will be in the detail.”

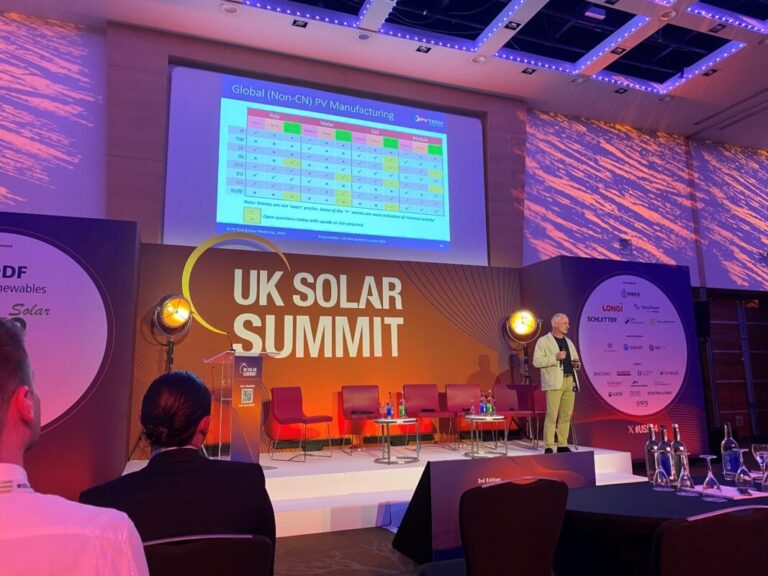

Amidst the global downturn in the silicon solar manufacturing industry, the UK holds a unique position according to Finlay Colville, head of research at our sister site PV Tech.

Colville outlined the global solar market trends—particularly those in the upstream and manufacturing sectors—that are impacting the UK market. He said the UK could benefit from being apart from the major solar trade blocs of the US, China and India, and leverage its relationships with them to attract the downstream industry.

Setting the stage

He began by outlining broad market trends that have shaped the current solar landscape. Chief among them is the “manufacturing downturn” unfolding in 2024 due to drastically low component and module prices, which Colville predicted on our sister publication, PV Tech, late last year. In a downturn—“driven by a lack of profitability in manufacturing”—manufacturers still need to supply the market, and so their priority becomes “cost, cost, cost,” he said.

Solar module costs are split between silicon and non-silicon across the supply chain. Colville says that the issue that caused the downturn was that in 2022-23, the industry expected non-silicon costs (those stemming from the ingot to module in the supply chain) to drop. They didn’t, and silicon costs from overwhelmingly Chinese polysilicon production had almost bottomed out already. This put huge pressure on the profit margins of module manufacturers and drove them to lower module prices however they could.

The second major factor is the emergence of trade disputes around the solar industry, particularly in the US and India, against China. In short (because the full story is long), the US has a number of trade tariffs on Chinese PV imports, most recently the emerging antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) tariffs, which may limit imports of solar cells from Chinese-owned companies operating in Southeast Asia to the US. Full coverage of this can be read on PV Tech.

India also has some import restrictions and domestic manufacturing incentives desiged to lessen its reliance on Chinese PV and foster domestic manufacturing capacity.

Turning to the UK

Colville suggests that the UK is simultaneously subject to the actions and moves of bigger market players and, perhaps, able to carve out its own niche. It’s a “good place to be for solar”, he said.

The price downturn and the ongoing trade disputes have seen supply start to shift, which has, in turn, changed the outlook for environmental, sustainability and governance (ESG) and traceability concerns for solar companies. Following the Sheffield Hallam report “In Broad Daylight”, focus turned to the allegations of human rights abuse and forced labour in the solar supply chain, as well as the carbon footprint of the components that make up a module.

A push for domestic manufacturing “changes the whole supply chain,” Colville said.

“How do you nurture domestic manufacturing? Either you just finance the whole sector, or you have to put barriers in to stop any product coming into the country at any cost. The US is choosing the second option…but it’s much more strategic in India.”

Both of these countries, regardless of their separate approaches, “are the only places driving policy that’s going to change traceability.

“Apart from products going into the US and India, everywhere else will buy products from China. The only other thing that’s driving traceability is corporate purchasing, where every company has an ESG department…and sets buying conditions.

“But they are nowhere near as detailed, as rigid, as comprehensive as what you get in countries where there are trade policies in place. It’s very superficial, it’s largely a box-ticking exercise.”

When it comes to supply, he points out that the UK represents 0.2% of the global demand for solar at the moment. “In isolation, it’s not a strong voice,” and it’s unlikely that any government will bother with the notion of UK solar manufacturing.

But with supply shifting, the UK occupies an advantageous place outside of the major blocs in the US, India and, latterly, Europe. “It’s a very mature buying market, there’s a lot of experience buying from different parts of the world,” Colville said, which in some respect makes it easier for the UK to get hold of traceable and plentiful solar modules.

“There is a lot of investment that has gone in from London and from corporate finance,” he said, and suggested that ESG practises could be pushed along and unlocked “but they’re not at the point where they’re competing with countries that have trade issues in place.”

“If you were to sell UK solar to the rest of the world, what would that look like? You’re not looking at competing with China for manufacturing, so there is actually a nice story to tell of a mature industry that’s grown and can do business with the other parts [of the world].”

“There is a uniqueness there.”

Today’s UK Solar Summit in London opened with an address from Sonia Dunlop, CEO of the Global Solar Council (GSC), in which she kicked off by saying solar is “growing like there’s no tomorrow … We will be the dominant renewable energy by the end of the decade.”

Beginning with discussions of the global market, she announced a plan to relaunch the GSC next Monday (10 June) with a number of initiatives to address the headline issues facing the solar industry: grid constraints and energy storage, geopolitical supply chain tensions, workforce shortages and the looming issue of end-of-life and recycling.

What will the election mean for solar?

Dunlop was then joined on stage by Chris Hewett, chief executive of Solar Energy UK, to discuss the outlook for the solar market ahead of the forthcoming general election next month. Their tone was largely optimistic, framing the UK as an outlier in its relative policy stability compared with the general shift to the right that is expected in much of the developed world later this year.

“The opposition leader has been talking about clean power and energy security,” Hewett said, “which is a very positive thing.” He caveated his enthusiasm with some concern over the rhetoric in Scotland, where he points to a “diving line” around the Scottish National Party (SNP) and the Conservative Party, saying that the green transition “will be bad for oil and gas jobs”.

Dunlop asked if there is a need to “redefine what energy security means” following Russia’s invasion of and subsequent war in Ukraine and the ensuing increase in gas prices. She asked how an anticipated Labour government might respond to this, given that traditional model of energy security has been “very focused on domestic oil and gas production, domestic fossil fuels.”

“There are parties out there talking about home grown [solar] energy as the way to deliver not just energy security but also the cheapest form of energy for citizens,” Hewett said. “I think that is a sea change. Solar, wind and batteries are going to be the backbone of any energy system across the world.”

Hewett continued and said that, for the fist time in his professional life, net zero and energy transition is “central to Labour’s economic offer”. The party has announced plans for GB Energy, a publicly-owned clean energy company-cum-green investment platform for private partnerships. Hewett said that this would be “part of the answer” to spurring investment into both renewables generation and grid infrastructure that the UK needs for its energy transition.

From a Conservative Party manifesto, Hewett said he is looking for a “nuanced policy”, and emphasised the need to work with both ruling and opposition parties to prevent solar being used as a political football.

“The last ministerial statement on planning and solar farms was spun to those who wanted to hear anti-solar farm rhetoric, but actually the planning policy did not change. There is a balance between how you use prime agricultural land and how you generate renewable energy in the rural economy. We’re looking for a nuanced policy in the Conservative manifesto.”

A ‘stable policy outlook’

Dunlop and Hewett discussed the apparently stable policy outlook for solar in the UK ahead of the election, in comparison with the uncertainties around the US race later this year and the upcoming European Parliament elections, which are widely expected to see a shift to the right.

“We can say that the UK has a very stable policy outlook, and that’s a great way of getting new investors to come and put their money here in GB”, Dunlop said.

However, Hewett said that the general public and media “does not understand quite how fast the energy transition is happening; what’s happening in China and the US.” He said that if the UK “resists” the pace of the energy transition “it will happen elsewhere and the ship will sail.”

Dunlop attributed some of this gap in understanding to the distributed nature of solar generation, whereby even large-scale solar farms, particularly in the UK, which does not deploy projects of the same scale as some more major markets, generate power in “much smaller chunks” than fossil fuels or wind generation.

“That means that, politically, we’re not as visible and not as well organised [as competitor technologies].”

Solar Energy UK’s manifesto

Hewett said that, ahead of the Labour party’s manifesto, his main request for an incoming government was “ambition on solar and energy storage.” He confirmed that Solar Energy UK would be releasing its own manifesto later this week.

“We have five areas to push,” he said. “One is politically embrace solar in the UK; that means being really clear about the planning system and really clear about the role for solar farms in the transition, and unapologetic about that.

“We want to see an increase in enthusiasm and push for the residential sector. The first step on that would be getting solar and energy storage mandated as part of the new build regulations,” by which he refers to the Future Homes Standard, which is currently under consultation.

“Grid, clearly. We want a massive transformation in the investment and the way that networks accept and deal with solar and storage.

“Skills. We know how much work needs to be done to train up the UK workforce to make sure as much of the economic benefit from this transition [as possible] gets used in the UK.

“Finally, reforming the market framework. The first step on that will be the Contracts for Difference (CfD).” The Allocation Round 5 (AR5) of the CfD scheme is due within the first few weeks of a new government taking power.”