Today, the same coal seams that attracted the attention of Australia’s first European settlers are still visible in the rocky outcrops of the Illawarra’s northern beaches, an hour’s drive south of Sydney. A little further south, in Port Kembla, the flames of the long-running steelworks burn through the night, and yet the region’s gum-covered slopes and picturesque coastlines are picture-postcard-worthy.

These small working-class towns, nestled between mountains and sea, have attracted an influx of ‘sea-changers’ over the past decade – including some of Australia’s most prominent spokespeople on climate and energy transition, including author Tim Flannery, inventor and entrepreneur Saul Griffith and TV star proponent of ‘just transition’ Yael Stone. They and others have pushed climate initiatives in the area, with postcode 2515 even selected to become Australia’s first all-electric suburb, although funding for that pilot project is now uncertain due to a recent change in government.

When the Electrify 2515 campaign began in 2022, led by Griffith’s decarbonisation website Rewiring Australia, it sought to sign up 500 local pilot homes within three months. That goal was achieved in just three days. “We were overwhelmed… everyone was really excited,” said Rewiring Australia mobilization and engagement manager Kristen McDonald.

When the Electrify 2515 campaign began in 2022, led by Griffith’s decarbonisation website Rewiring Australia, it sought to sign up 500 local pilot homes within three months. That goal was achieved in just three days. “We were overwhelmed… everyone was really excited,” said Rewiring Australia mobilization and engagement manager Kristen McDonald.

The Illawarra region has a long relationship with the energy industry. This, combined with the port and transport infrastructure and the vibrant conversation around energy transition, has led to the region being designated as one of New South Wales (NSW)’s five renewable energy zones. In August 2023, the Federal Government went a step further and proposed a 4.2 GW offshore wind development zone, covering 1,461 km² of ocean, from Wombarra to Gerringong, 10 km to 30 km offshore.

Unexpected opposition

In the days and weeks that followed, outrages erupted on social media. Painted signs reading ‘Not on our shores’ were plastered across beach car parks and a series of superimposed images implying wind turbines would look like Eiffel Towers on the sea were collected by community groups on the social media platform Facebook. Only weeks later, in October 2023, did formal community consultation begin at town hall. By then, disinformation had already engulfed the discussion, creating a quagmire in which facts and figures from institutions including the local University of Wollongong and the Maritime Union of Australia were often lost.

“The opposition took us by surprise,” Stone said. Four months earlier she had launched the Illawarra initiative Hi Neighbour, aimed at training coal sector workers and young workers from other industries for roles in renewable energy. Like Electrify 2515, the initiative received a positive response and support steadily grew, but Stone’s visibility in renewable energy led to her being threatened during the peak of precipitation in the Wind Zone. “I was very naive about the community’s embrace,” she said, of the wind farm plans. “I could not have anticipated how intense the debate would be… it was a shocking and frightening time.”

But mixed with inaccurately scaled images and vocal opposition, community members also raised important questions about whether the money invested in the wind site and the energy generated would remain in the local area and, more importantly, who exactly would control the maritime activities would perform. studies for the still new floating wind projects. That indicated a clear conflict of interest, as project proponents historically led such studies. I grew up in the Illawarra and the area’s famous whale migration was part of our official primary school song. Whenever someone spied a humpback whale breach from our school window, the class would pause so we could all admire the procession.

Communities on this coast love the unique natural environment – something that is true of many regions, where potato farms and rivers are becoming embedded in people’s core identities. In the Illawarra, whales have become something of a proxy, with opponents of renewable energy development using a real desire to protect beloved wildlife to shift the debate to blind fear. That has allowed right-wing claims that wind farms will be “whale graveyards” to take root in a staunchly progressive region, with accusations spiraling out of control online before calm counterarguments can be voiced. “It gives me chills to see Donald Trump’s statements echo in our small town,” Stone said.

Rewiring Australia’s McDonald said that “it was difficult to convey some of the nuances of the process where people should focus their energy.” She noted that most renewable energy advocates share concerns about the environmental impact of major projects. “Instead, it has been much simplified and the education side has not been as strong as it should be, so there is a kind of fear-based campaign that plays on people’s insecurities, which are valid,” she added. “As humans, we relate to what we can see, touch and feel, and sometimes we do [climate change] is a bit too abstract.”

Bush uprising

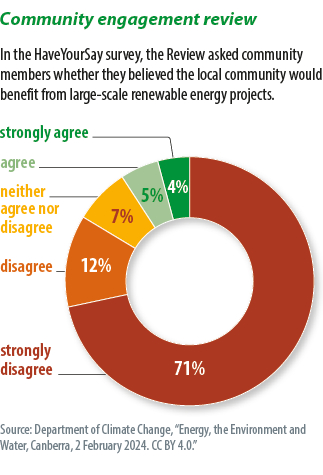

The emotionally charged scenes set in the Illawarra have parallels across the country, so much so that the phenomenon has been dubbed Australia’s ‘bush uprising’. With large-scale renewable energy and transmission projects set to boom over the next six years thanks to new government procurement auctions, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese commissioned a formal Community Engagement Review for Sustainable Energy in July 2023. from Australia’s Energy Infrastructure Commissioner Andrew Dyer were made public in February 2024 and painted a picture of an underperforming sector.

“For many developers, the skills, experience and knowledge of engagement staff and management are below community expectations, as are their support processes, collateral and overall management of the developer engagement function,” the review said.

Dyer held dozens of meetings with representative stakeholders, landowners and community groups, and received more than 500 written submissions and more than 250 responses to online surveys – with most respondents living near proposed renewable energy and transmission projects under development. Specifically, 92% of respondents were dissatisfied with developers’ community involvement, and 85% were dissatisfied with the explanations and answers provided by developers. While the report focused on the private sector clean energy sector, it is worth noting that community frustration also extended to government-led renewable energy plans.

The evaluation resulted in six recommendations, all of which have been accepted by the federal government. They include establishing a “suitably qualified and experienced independent body or individual to design, develop, implement and operate a developer rating system.” As we assess developers’ practices and history, the rating system will be launched on a voluntary basis, but Dyer recommended considering participation in government tenders. He also advised authorities to investigate developers before allowing them to submit plans outside auction programs. This practice is intended to reduce the growing ‘consultation fatigue’ that many communities are experiencing, especially around renewable energy zones.

Dyer urged states and territories to provide maps showing where renewable energy and transmission projects are suitable – including ‘no-go’ zones – and to establish a new ombudsman charged with handling complaints during all project phases, with the developers having to bear the costs. The commissioner also recommended formal processes for community benefit sharing and communications programs – a theme that has been a focal point for Nicole Walton, director of engagement and change consultancy at Aurecon, a design, engineering and consultancy firm.

Build trust

Walton said it’s crucial that developers start building trust. She proposed a visualization with an equilateral triangle in which empathy, authenticity and logic must be balanced. That means communicating in a way that recognizes community perceptions, is transparent and clear, and recognizes that different segments of the community need different degrees of information. While such an infographic may be sufficient for some, others want technical project details in appropriate and digestible formats.

Winning community acceptance, Walton said, involves explaining a two-part story to help communities understand not only that the energy transition is happening, but what it looks like at the state and local level. People need to understand how projects benefit them, says Peta Ashworth, director of Curtin University’s Institute for Energy Transition.

The specific path to acceptance, according to Walton, starts with ensuring communities understand climate impact. Then developers must understand community perceptions, create a plan to address those beliefs, adapt that plan as they discover what the community specifically wants and needs, and then demonstrate that they have responded to those local desires.

Finally, Walton said it is critical that developers provision and integrate their community engagement teams.

“The engineering team relies on the community team to get that social license; The community engagement team relies on the technical team to have the content to acquire the social license – so they cannot operate in isolation from each other, although they often try,” she said. “Engaging the right people at the right time with the right message – all these things need to be taken into consideration and they are just as important as your marine studies.”

She said they are just as important as flora and fauna studies, and just as important as the design of the actual plant, “because without community acceptance your project can collapse. It’s just a change in mentality.”

This content is copyrighted and may not be reused. If you would like to collaborate with us and reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.